The KIM-5 Resident Assembler

A couple of weeks ago, Hans Otten published the sources of the Resident Assembler and Editor ROMs of the KIM-5 board. They run with his KIM-1 emulator, so it was time to have some fun with it.

Complete info and documentation at Hans’ site: http://retro.hansotten.nl

Source code for the example programs and utilities used here at my GitHub repository.

Testing environment

I’ll be using the excellent KIM-1 Simulator by Hans Otten. Be sure to get the latest version, 1.5.1.

Download the ROM dumps archive also from Hans’ site. Load the kim5.bin file into $E000:

For running the test program, also enable the MTU K-1008 Visible Memory at $A000-$BFFF in the settings:

The assembler

It is a very simple, single-pass assembler, so it is not very well suited for large or complex programs. It resides in ROM from address $E000 and assembles directly to the destination addresses. At first glance, it supports some basic but useful features:

- Labels: 6 char length maximum.

- Comments: anything after the last operand in a line or after a semicolon is a comment.

- Expressions: addition, substraction, multiplication and division, and

>(get high byte) and<(get low byte) are supported, but not bitwise operations. - Directives:

.BYTE,.WORD,.OPT,.ENDand=. The last one is used with*to set the program counter and reserve memory. - Constants: Decimal, hexadecimal

$, octal@, binary%and ASCII litearal'are supported.

Note that the ASCII literal is preceded by the apostrophe, not enclosed in them.

Before using it, it needs to reserve 8 bytes of memory for each symbol (labels and constants) it is going to use. You need to set the start and end of the reserved area at zero-page addresses $DFand $E1. For simplicity, let’s reserve the 4K area from $2000 to $2FFF:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

KIM

0000 xx 00DF

00DF xx 00.

00E0 xx 20.

00E1 xx FF.

00E2 xx 2F.

00E3 xx

The editor

The entry point is at $F100, and first thing it asks is the base address in hexadecimal(where the source is stored), and wether it is a New or existing (Old) program . Let’s use 3000, select Nand then enter S to start the editor:

1

2

3

4

5

6

00E3 00 F100

F100 20 G

BASE=3000

N OR O?N

S

3000 0000 0000

The editor works pretty much like the Basic editors of popular 8-bit computers like the Vic-20: Enter a line number first (between 1 and 9999) and then the line text. It supports saving and loading to cassette and reading and punching to paper tape.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

3000 0000 0000

10 ; This is a comment

20 *=$200

30 LDA #0

40 BRK

50 .END

P A

0010 ; This is a comment

0020 *=$200

0030 LDA #0

0040 BRK

0050 .END

*ET

P A prints the program, let’s assemble it using A:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

LINE # LOC CODE LINE

0010 0200 ; This is a comment

0020 0200 *= 200

0030 0200 A9 00 LDA #0

0040 0202 00 BRK

0050 0203 .END

ERRORS = 0000

SYMBOL TABLE

END OF ASSEMBLY

KIM

F100 20

It is a useless program, of course, but enough to know that it will be tedious to type anything longer and also adequate to see how the editor stores the program internally.

The editor format

Let’s inspect the memory starting at our base address ($3000):

The first thing we see if that line numbers are stored as BCD words. Then, the content of the line follows verbatim, there is no tokenization of the opcodes or directives. Each line is terminated by a carriage return, $0D, and the end of file is marked by $1F.

Saving programs

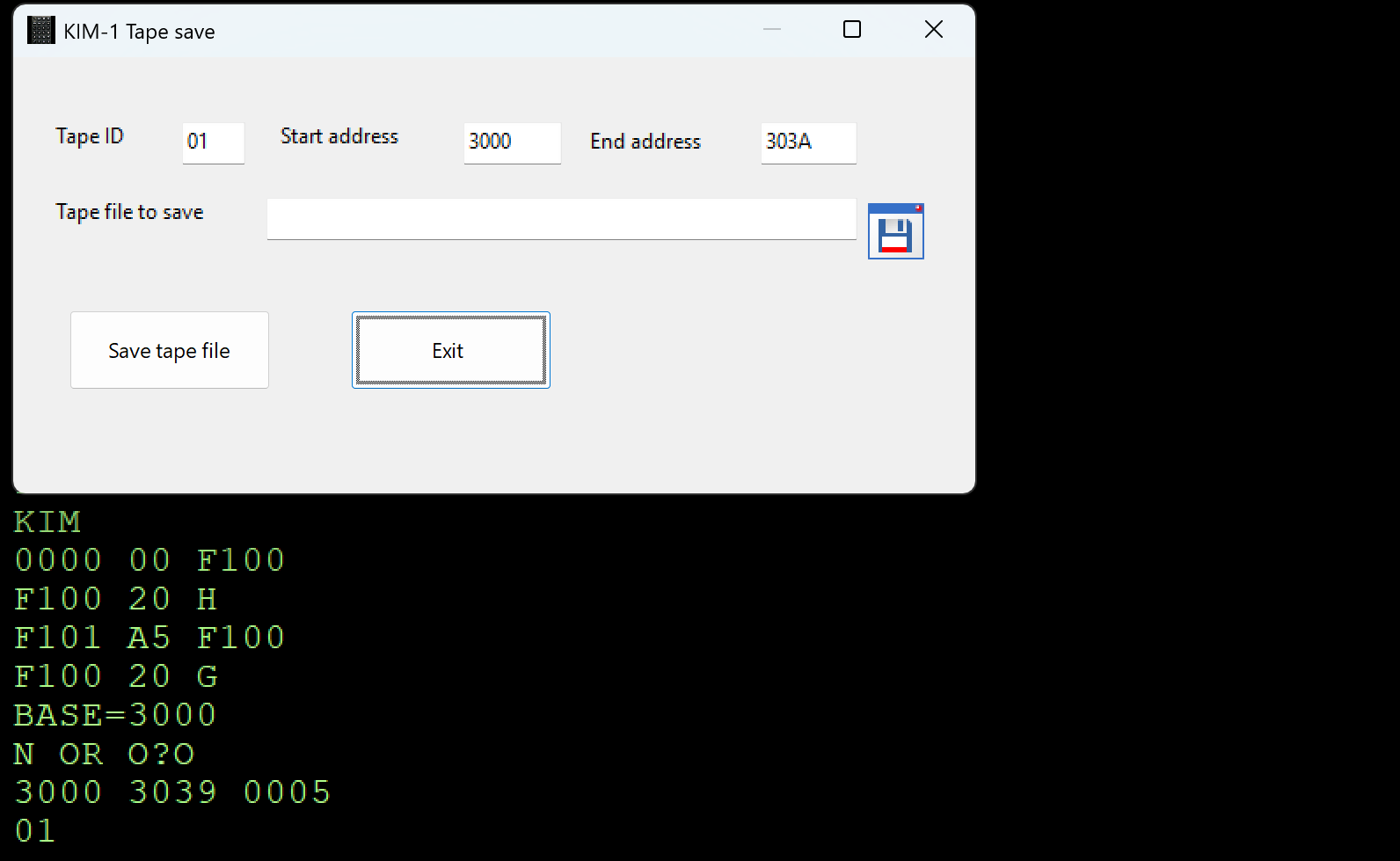

So we know how the programs are stored in memory but, how are they saved on cassette? Let’s return to the editor, telling it that now we have a pre-existing program in memory:

1

2

3

4

5

KIM

F100 20 G

BASE=3000

N OR O?O

3000 3039 0005

3000 is the vase address, 3039 is the end of the program and 0005is the number of lines.

To save the current program on tape, press and mantain pressed the CTRL key, strike T, release CTRL and type the tap index, 01in this case:

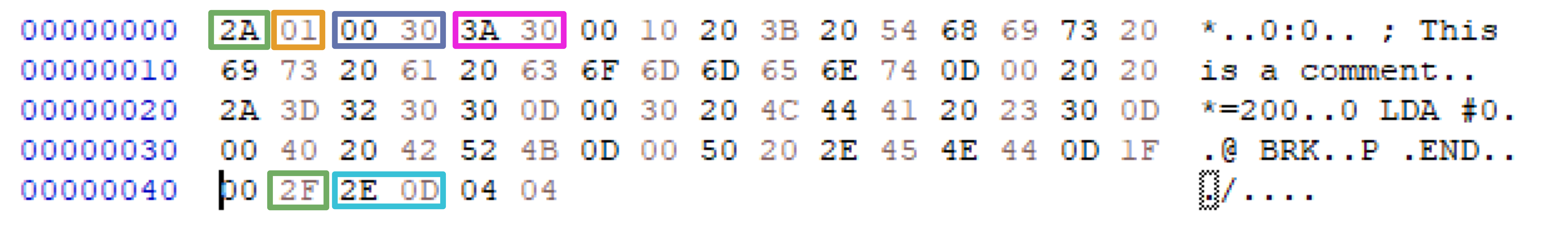

Let’s see what is in the TAP file:

2Ais the TAP header, 01 is the index, 00 30and 3A 30 are the start and end addresses of the data in little endian format (Notice that the editor is saving an extra byte up to $303A, instead of $3039), 2F marks the end of data, 2E 0D is the checksum and then some trainling 04’s to mark the end of the file.

So, just a normal TAP file.

The utilities

With the information above, we can now write a couple of utilities to transfer plain text programs from our PC to the KIM-5 editor and vice versa.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Usage: asc2kim5 [-h] [-f {bin|tap} [-a <address>] [-i <num>]] [-l <num>] <input_file> <output_file>

Arguments:

input_file Plain text file

output_file Binary output file

Options:

-h | --help Show this help message and exit

-f | --format {bin|tap} Specify output file format. Default is binary

-a | --address <address> Load address. Mandatory for TAP, ignored for BIN

-i | --id <num> Tape index. Ignored for BIN, default is '01'

-l | --line-increment <num> LLine number increment. Default is 10

Outputs the space requirements for the symbol table.

The input file is a plain text one, created with any text editor, in KIM-5 Resident Assembler syntax, without line numbers. Those are automatically generated starting in 10, with increments of 10. This can be changed with the -l option.

The output can be a binary or tap file. In the latter case, the load address is mandatory and a tape index can be specified. If not, defaults to 01.

Examples

Create a file with a text editor:

1

2

3

4

5

; This is a comment

*=$200

LDA #0

BRK

.END

1

2

$ asc2kim5 -f tap -i 02 -a 0x3000 test.asm test.tap

Total number of symbols: 0, reserve 0 (0x0000) bytes for symbol table

Load into the KIM-1:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

KIM

0000 00 17F9

17F9 00 02.

17FA 00 1873

1873 A9 G

KIM

0000 00 F100

And check that it is really there:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

KIM

0000 00 F100

F100 20 G

BASE=3000

N OR O?O

3000 304A 0005

P A

0010 ; This is a comment

0020 *=$200

0030 LDA #0

0040 BRK

0050 .END

*ET

Now, let’s go the other way around:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Usage: kim52asc [-k] [-i <num>] <input_file> <output_file>

Arguments:

input_file TAP format input file

output_file Plain text output file

Options:

-h | --help Show this help message and exit

-k Keeps line numbering in the output file

-i | --id Tape index. Issues warning if don't match

1

2

3

$ kim52asc -i 0x66 -k test.tap test.asm

Warning: Tape IDs do not match: 02

Saved from 0x3000-0x304B

And this is the generated file:

1

2

3

4

5

10 ; THIS IS A COMMENT

20 *=$200

30 LDA #0

40 BRK

50 .END

Putting it all together

Now, let’s port this little program I wrote a while back. It uses a sieve algorithm to find the primes between 1 and 127999 and uses a K-1008 Visable Memory Card to follow its progress viaually.

It is written in ca65 assembly, so the first step is to replace the construct specifics of that variant with its KIM-5 Resident Assembler equivalents:

All caps.

Shorten all symbols to 6 characters maximum and no special symbols.

No colon

:after labels.-

Remove unsupported directives:

.ifndef,.endifor.assert.Replace

.segmentwith*=. Replace.reswith*=*+. No parenthesys in expressions. They are resolved from left to right.

-

We are also adding the following directive to the top of the file to disable listings and only print errors and the symbol table:

1

.OPT ERRORS, NOLISTING, SYMBOLS

And that should be it. Let’s write the changes to the test1.asm file and convert to tap:

1

2

$ asc2kim5 -f tap -a 0x3000 -i 01 test1.asm test1.tap

Total number of symbols: 22, reserve 176 (0x00B0) bytes for symbol table

Reserve space for the symbol table and load the program to the KIM-1:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

KIM

0000 00 DF

00DF 00 00.

00E0 00 20.

00E1 00 FF.

00E2 00 2F.

00E3 00 17F9

17F9 00 01.

17FA 00 1873

1783 A9 G

Assemble it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

0000 00 F100

F100 20 G

BASE=3000

N OR O?O

3000 4262 0155

A

And we get a bunch of errors. The first surprise is that, although stated otherwise in the documentation, multiplication is not supported in expressions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

KIMASM

LINE # LOC CODE LINE

0190 0200 20 71 02 NPIX = NX*NY ; NUMBER OF PIXELS

***ERROR # 13 ^

0670 0231 A1 00 00 LDA #>NPIX-1 COMPARE TO SCREEN SIZE

***ERROR # 13 ^

0710 023C A1 00 00 LDA #<NPIX-1

***ERROR # 13 ^

1080 027A 61 00 00 ADC #NPIX/8/256

***ERROR # 13 ^

1160 028B C1 00 00 CMP #<NPIX/8

***ERROR # 13 ^

ERRORS = 0005

SYMBOL TABLE

VMORG A000 NX 0140 NY 00C8 FIRST 0003

LAST 0165 ADP1 00A0 CNDATE 00A2 CNDP 00A4

BTPT 00A6 FILSCR 0271 CHECK 020B PIXADR 0295

MSKTB1 02B7 NEXT 0255 CLRMUL 0224 NPIX ****

CLRMU1 0244 MSKTB2 02BF ISBGR 0261 DONE 0270

SET1 027E SET2 0289

END OF ASSEMBLY

Error #13 is “Invalid expression in operand”. The first one is caused by the * symbols. The next ones may be because NPIX has not been evaluated.

As NX and NY are just used for calculating NPIX, just replace the expression with the actual number and save the changes to test2.asm

1

2

3

; NX = 320 ; NUNMBER OF BITS IN A ROW

; NY = 200 ; NUMBER OF ROWS

NPIX = 64000 ; NUMBER OF PIXELS

Load the new program and try again:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

LINE # LOC CODE LINE

0710 023B A1 A1 00 LDA #<NPIX-1

***ERROR # 18 ^

1080 0279 61 61 00 ADC #NPIX/8/256

***ERROR # 13 ^

1160 028A C1 C1 00 CMP #<NPIX/8

***ERROR # 13 ^

ERRORS = 0003

SYMBOL TABLE

VMORG A000 NPIX FA00 FIRST 0003 LAST 0165

ADP1 00A0 CNDATE 00A2 CNDP 00A4 BTPT 00A6

FILSCR 0270 CHECK 020B PIXADR 0294 MSKTB1 02B6

NEXT 0254 CLRMUL 0224 CLRMU1 0243 MSKTB2 02BE

ISBGR 0260 DONE 026F SET1 027D SET2 0288

END OF ASSEMBLY

This time, we hit with an “Illegal operand type for this expression” error. So it does not like the #<NPIX-1 construction but, oddly, takes without problems LDA #>LAST+1 a few lines below ![]()

The other two errors are expected. If it does not support mutiplication, makes sense it does not support division either.

Let’s make a few modifications to the program and save it to test3.asm:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

NPIX = 64000 ; NUMBER OF PIXELS

NPIXM1 = NPIX-1 ; NUMBER OF PIXELS

NBYTE = 8000 ; NUMBER OF BYTES (NPIX/8)

FIRST = 3 ; FIRST CANDIDATE TO CHECK

...

; LDA #>NPIX-1 COMPARE TO SCREEN SIZE

LDA #>NPIXM1 COMPARE TO SCREEN SIZE

...

; LDA #<NPIX-1

LDA #<NPIXM1

...

; ADC #NPIX/8/256

ADC #>NBYTE

...

; CMP #<NPIX/8

CMP #<NBYTE

And give it a go:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

LINE # LOC CODE LINE

ERRORS = 0000

SYMBOL TABLE

VMORG A000 NPIX FA00 NPIXM1 F9FF NBYTE 1F40

FIRST 0003 LAST 0165 ADP1 00A0 CNDATE 00A2

CNDP 00A4 BTPT 00A6 FILSCR 026F CHECK 020B

PIXADR 0291 MSKTB1 02B3 NEXT 0253 CLRMUL 0224

CLRMU1 0242 MSKTB2 02BB ISBGR 025F DONE 026E

SET1 027B SET2 0286

END OF ASSEMBLY

So far, so good. Let’s give it a try. Remember to enable the K-1008 Visible Memory option in the simulator at $A000-$BFFF and run the program:

1

2

3

KIM

F100 20 0200

0200 20 G

Success!

Conclusions

The KIM-5 Resident Assembler has the usual limitations of a one-pass assembler in a resource constrained computer, like:

Limited support of forward references.

No macro support.

Very limited arithmetic expressions and absence of bitwise ones.

But it also shows some inconsistent behaviour:

Despite the documentation saying otherwise, multiplication and division are not working.

Some constructions like

#<LABEL+1work in operands, but not#<LABEL-1.

Another oddity I’ve found is the way it manages the forward references. When the assembler can’t resolve a reference in an operand, it always reserve two bytes. That is logical for instructions that have absolute or page zero addressing modes, as it can end being a one or two bytes value. But for instructions that only have relative addressing, like all the branches, it does not make sense, because it will always resolve to a one byte value or an error. In these cases, the assembler places the value in the first byte and a NOP in the second, wasting one byte and two clock cycles for every relative forward jump. Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

; Expected Generated

BCS LE054 ; E044 B0 0E E044 B0 0F <--- LE054 is a forward reference

; E046 NOP <--- Added NOP

SED ; E046 F8 E047 F8

LDA LINEL ; E047 A5 4D E048 A5 4D

ADC #$01 ; E049 69 01 E04A 69 01

STA LINEL ; E04B 85 4D E04C 85 4D

LDA LINEH ; E04D A5 4C E04E A5 4C

ADC #$00 ; E04F 69 00 E050 69 00

STA LINEH ; E051 85 4C E052 85 4C

CLD ; E053 D8 E054 D8

LE054 JSR NFNDNB ; E054 20 E1 E5 E055 20 54 E6

I can’t imagine developing a non-trivial program on a KIM-1 using this tool. Programmers in the 70s where cut from a different cloth!